Go监控模式(Monitor Pattern)

Go 能实现监控模式[1],归功于 sync 包和 sync.Cond 结构体。监控模式允许 goroutine 在进入睡眠模式前等待一个定特定条件,而不会阻塞执行或消耗资源。

条件变量

我们举个例子,来看看这个模式可以带来的好处。我将使用 Bryan Mills 的演示文稿[2]中提供的示例:

type Item = int type Queue struct {

items []Item

*sync.Cond

} func NewQueue() *Queue {

q := new(Queue)

q.Cond = sync.NewCond(&sync.Mutex{})

return q

} func (q *Queue) Put(item Item) {

q.L.Lock()

defer q.L.Unlock()

q.items = append(q.items, item)

q.Signal()

} func (q *Queue) GetMany(n int) []Item {

q.L.Lock()

defer q.L.Unlock()

for len(q.items) < n {

q.Wait()

}

items := q.items[:n:n]

q.items = q.items[n:]

return items

} func main() {

q := NewQueue()

var wg sync.WaitGroup

for n := 10; n > 0; n-- {

wg.Add(1)

go func(n int) {

items := q.GetMany(n)

fmt.Printf("%2d: %2d\n", n, items)

wg.Done()

}(n)

}

for i := 0; i < 100; i++ {

q.Put(i)

}

wg.Wait()

}

Queue 是一个非常简单的结体构,由一个切片和 sync.Cond 结构组成。然后,我们做两件事:

- 启动 10 个 goroutines,并将尝试一次消费 X 个元素。如果这些元素不够数目,那么 goroutine 将进去睡眠状态并等待被唤醒

- 主 goroutine 将用 100 个元素填入队列。每添加一个元素,它将唤醒一个等待消费的 goroutine。

程序的输出,

4: [31 32 33 34] 8: [10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17] 5: [35 36 37 38 39] 3: [ 7 8 9] 6: [40 41 42 43 44 45] 2: [18 19] 9: [46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54] 10: [21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30] 1: [20] 7: [ 0 1 2 3 4 5 6]

如果多次运行此程序,将获得不同的输出。我们可以看到,由于是按批次检索值的,每个 goroutine 获取的值是一个连续的序列。这一点对于理解 sync.Cond 与 channels 的差异很重要。

sync.Cond vs Channels

用单个 channel 解决这个问题并不容易,因为它会被消费者一个接一个地拉出来。

为了解决这个问题,Bryan Mills 编写了一个包含两个通道组合的等价解决方案(第 65 页)[3]:

type Item = int type waiter struct {

n int c chan []Item

} type state struct {

items []Item

wait []waiter

} type Queue struct {

s chan state

} func NewQueue() *Queue {

s := make(chan state, 1)

s <- state{}

return &Queue{s}

} func (q *Queue) Put(item Item) {

s := <-q.s

s.items = append(s.items, item)

for len(s.wait) > 0 {

w := s.wait[0]

if len(s.items) < w.n {

break }

w.c <- s.items[:w.n:w.n]

s.items = s.items[w.n:]

s.wait = s.wait[1:]

}

q.s <- s

} func (q *Queue) GetMany(n int) []Item {

s := <-q.s

if len(s.wait) == 0 && len(s.items) >= n {

items := s.items[:n:n]

s.items = s.items[n:]

q.s <- s

return items

}

c := make(chan []Item)

s.wait = append(s.wait, waiter{n, c})

q.s <- s

return <-c

}

结果类似:

1: [ 0] 10: [ 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10] 5: [11 12 13 14 15] 8: [16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23] 6: [24 25 26 27 28 29] 3: [37 38 39] 7: [30 31 32 33 34 35 36] 9: [46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54] 2: [44 45] 4: [40 41 42 43]

在可读性和语义方面,条件变量在这里可能有一个小优势。但是,它也有限制。

注意事项

我们运行包含 100 个元素的基准测试,如示例所示:

WithCond-8 15.7µs ± 2% WithChan-8 19.4µs ± 1%

在这里使用条件变量要快一些。让我们试试 10k 个元素的基准测试:

WithCond-8 2.84ms ± 1% WithChan-8 917µs ± 1%

可以看到 channel 的速度要快得多。Bryan Mills 在“饥饿”部分(第 45 页)[4]中解释了这个问题:

假设我们调用 GetMany(3000) 的同时有一个调用者在密集的循环中执行 GetMany(3)。两个服务可能几乎同时醒来,但 GetMany(3) 调用将能够消耗三个元素,而 GetMany(3000) 将没有足够的元素就绪。队列将保持耗尽状态,较大的调用将一直阻塞。

该演示文稿还强调了在处理条件变量时我们可能面临的其他问题。如果模式看起来很简单,我们在使用它时应该小心。之前看到的例子向我们展示了如何更有效地使用 channel 并通过通信进行共享。

内部流程

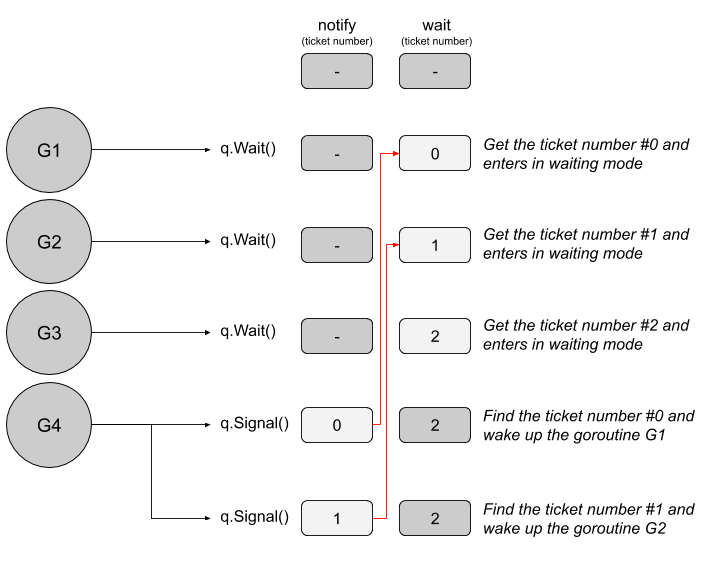

内部实现非常简单,基于发号系统。以下是上一个示例的简单表示:

进入等待模式的每个 goroutine 将从变量 wait 开始分号,该变量从 0 开始。这表示等待队列。

然后,每次调用 Signal() 都会增加另一个名为 notify 的计数器,该计数器代表需要通知或唤醒的 goroutine 队列。

我们的 sync.Cond 结构包含一个负责发号的结构:

type notifyList struct {

wait uint32 notify uint32 lock uintptr head unsafe.Pointer

tail unsafe.Pointer

}

这是就是上面提到的 wait 和 notify 变量。该结构还通过 head 和 tail 保存等待的 goroutine 的链表,其中每个 goroutine 在其内部结构中保持对所获取的票号的引用。

当收到信号时,Go 会在链表上进行迭代,直到分配给被检查的 goroutine 的票号与notify 变量的编号匹配,如匹配则唤醒当前票号的 goroutine。一旦找到 goroutine,其状态将从等待模式变为可运行模式,然后在 Go 调度程序中处理。

- nagios被动监控模式

- 一段监控cli模式下运行php十分正常运行的shell脚本

- Zabbix Agent active批量调整客户端为主动模式监控

- Go Builder 建造者模式

- 使用Grafana监控Go应用

- Go---设计模式(策略模式)

- zabbix使用zabbix_java_gateway 监控java应用进程 主动模式 python脚本

- 【寒江雪】Go实现观察者模式

- php前端+go后端模式探索

- 使用GO语言开发 Redis数据监控程序

- Go 单例模式[个人翻译]

- GO实现文件夹监控

- CS模式短信监控系统的设计与实现 (转)

- Zabbix Agent active批量调整客户端为主动模式监控

- 集团监控平台前端解密之夜间模式

- Linux监控平台(主被动模式,添加监控主机,添加图形,处理图形乱码,远程执行命令)

- Go Facade外观(门面)设计模式

- 流模式的服务器监控页面

- Go --- 设计模式(模板模式)

- JDK5和JDK6对JMX的ObjectName模式支持的不同(监控应用服务器系列文章)